.jpg)

Table

of Contents

Flash Interview:

1. Ira Sadoff

Poetry:

1. Bite, Danny Rendleman

2. Cat, Danny Rendleman

3. In Wartime, Danny Rendleman

4. House of Lost Causes, Dinah Berland

5. Falling Out of Love, Dinah Berland

6. Exit Row, Dinah

Berland

7. At the Airport, Steven Rydman

8. La Fin du Monde, Steven Rydman

9. Suppose at Twelve, I Am Not a Boy, Steven

Rydman

10. Like Eyes of the Tapster, Jonathan Hayes

11. Father, Jonathan Hayes

12. Harvest Moon, Jonathan

Hayes

13. Fugue, Athena Kildegaard

14. Armadillo, Athena Kildegaard

15. Deaf Smith County, 1932, Athena Kildegaard

16. Roosters, Athena Kildegaard

17. Conscience Is Never Kind, Joseph Lisowski

18. Not The Best Way To Wake Up, Joseph

Lisowski

19. The Warrior for Life, Rebecca Seiferle

1.

Love Potion Tumbler Find, Jnana Hodson

Photography:

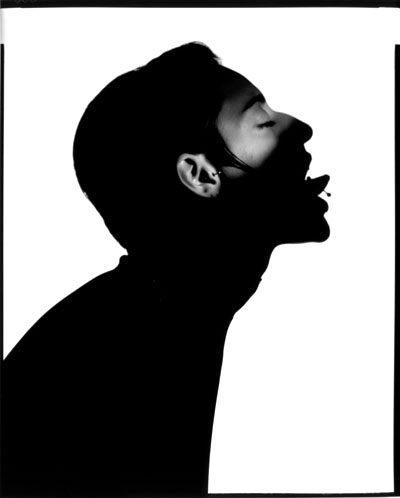

1. Untitled, Peter Hobbs

2. Untitled, Peter Hobbs

3. Untitled, Dong Soo Choi

4. Untitled, Dong Soo Choi

Bios

Info & Submission Guidlines

Editors

Links

Archives:

1.

Spring 2003

![]()

IRA SADOFF

The Dana

Professor of Poetry at Colby College,

Ira

Sadoff is the author of seven collections of poetry (most recently BARTER,

U. of Illinois), a novel, O.Henry prize-winning short stories, and The

Ira Sadoff Reader (a collection of stories, poems, and essays about contemporary

poetry). He is the recipient of a Creative Arts Fellowship from the National

Endowment of the Arts and a Fellowship from the Guggenheim foundation.

He has published critical articles about postmodern American poetry and

is interested in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century American Poetry.

1.

Is there a window where you write, and, if so, what can you see from it?

I have a small studio behind my house (one room with a heater). We live

on a hill and in the fall and winter I can see down to the Kennebec River.

In the spring and fall there's lots of foliage to protect us from our

neighbors who think Halloween is Satan's holiday. There's a quince tree

and there's our house, which is old and New England-y.(You can see the

studio on my website www.colby.edu/~isadoff/personal. html).

2. If God or a superhero offered to let you trade your gift (poetry)

in for another, perhaps more lucrative, talent, would you? What would

you want instead?

If I were fourteen I'd want to be an outfielder with the Yankees,

but I can't imagine any other talent that could sustain me like poetry.

If I didn't know better I might think playing music, but I think I honestly

enjoy listening to music more. So I feel very blessed with my gifts, however

limited they might be.

3. What outside activities, sports, or hobbies do you engage in

that you feel feed your creativity?

Listening to music, drinking and talking with friends, reading, traveling.

4. What is your favorite line, written by someone else?

I DON'T HONESTLY HAVE ONE. There's something about Merwin's "This

must be what I wanted to be doing," for all its ambiguity, I find

attractive. For pure beauty, it's hard to top Lorca's "When the moon

rises, the heart feels/like an island in Infinity."

5. What line/s of your own poetry are you most surprised by or

proud of?

Those feelings change, but TODAY I do like the leaps in "Self-Portrait

with Critic," from BARTER:

But passing is nobody's business, who you are

is a secret to everyone, that's American

as being an exception, believing in

your own invention, tinkering around

in a minor key since nobody's listening.

6. How political do you think the business of poetry is?

How political is being a sexual being, is going to the store, is believing

in transcendence? I see political in terms of relational and struggles

with power in culture. Some of us can insulate ourselves from the most

obvious aspects of culture, but at a cost to ourselves and others. We

live in a world where public and private life seem distant and segregated,

but it's more a reflection of our powerlessness as individuals. As a result,

many of us feel we can only find happiness and purpose inside our families

or with our friends. The result is a much larger loneliness and numbness,

a kind of costly repression that alters our capacity to be compassionate

and loving human beings.

7. Is there a writing conference you'd actually recommend?

Not unless you're feeling very isolated and want to use the conference

as a way of making a connection with other poets and learning a handful

of things, such as finishing out who others are reading, etc. If you want

to become famous, or you want to learn substance I'd almost always advise

a class, which involves an ongoing process and, if you're lucky, good

rigorous mentoring.

8. Does teaching inform or detract from your own writing?

Yes. It takes an enormous amount of time because I take it seriously and

love my subject. It's humanizing to have a connection with people just

forming their identities and asking important questions. And best of all,

I get to read literature carefully that influences my work. Most recently,

after teaching Whitman, I finally found a way could use him as a writer.

9. What advice about writing would you give someone just starting

out?

Sustain a passion for the process, listen well, be patient, think of poetry

writing as a mission and not a career. You may not end up being the best-known

poet, but you won't forget why writing matters.

10. What advice about the world?

Advice is tricky, and I increasingly feel better about living with uncertainty

and contingency, how wherever you are will be shortly changed. But I would

say, listen hard to enter another person's heart. Be generous, be prepared

to temper ideals and principles with experience. Be prepared to change

your mind often.

Personal Web

Page

About

BARTER

![]()

Danny

Rendleman

BITE

I flick

the spider up off the top of the page of the Sunday Times,

Hoping it will discover wings, alight gradually into the hostas, say,

Or, failing that, not descend once again into my sight.

It discovers my arm. I had thought I launched it in a parabola, but

No, straight up, straight down, into the down of my forearm, curly

And probably longer-lived than this spider, longer-grown.

I’ve heard all spiders bite. I’m not about to test the theory:

But what to do? Smear it down along the muscle, shake it off

Like a bad memory, bad dream, omen? Welcome it into my already

Shaky life, bereft so suddenly of wife, pet, future? Right.

The remaining

cat might have something to say about that;

The void I’ve accidentally created might object, too.

Curious creature, though—barely a jot of protoplasm, curious,

Adamant at being—sentient, I gather. The sunset has been

A letdown, this cabernet less than promised, no messages.

They say the stars are spiraling around us. Something within us

Might be a center of appeal, not to say attraction. Maybe I’m it.

Failing a better god, a luckier landing site—I could hope the spider

Has chosen me, exactly, wise spider that he is. A Copernicus spider!

How glad I am, how glad he is that my flick of an index

Finger did not cripple him beyond redemption, that he

Went up and up and up into the lilac-blent, new-cut grass blur

Of air, only to fall back and back and back onto me.

Unto me. Mine.

![]()

Danny

Rendleman

CAT

He knows

not what we do. He is too old.

Having hung around me long enough, biting his toes,

Slit in his ear from some backyard to and fro,

He has bourbon in his veins, silk in his innards,

So many plodding doves beneath his claw—

So he asks pardon from a father only he can conjure,

The arcane aches in his fat belly, too many mistresses

Who have itched his chin, worried over his diet,

Gone when he awakes stretching in the hallway sun.

Or asks for his mother, maybe, that heathen, ingrate,

Alley harlot who abandoned him like a sweetmeat.

He yowls at all we think we’ve overcome, left,

As we imagine we’ve been cruel in some way yet

To be construed, tabulated, of import.

Such cat talk.

Then, he forgives, forgets, pauses like an andiron

At the door. Looks out to seas we won’t ever know,

Looks up the stairs and asks to be chased,

Thus. And, again, thus. Until he ascends.

![]()

Danny

Rendleman

IN WARTIME

for Jan

1.

She thinks she may have a button

To fit my shirt. White. She thinks she has

A whole bag full. Someone I’ve never met

Sends me advice from Flannery O’Connor.

There aren’t any jets out my window.

I have to run errands tomorrow—

Credit union, cleaners, salad greens, stuff.

We have the fruit cellar, enough water,

Perhaps, blankets, though it is spring out there.

We stepped out one night

And saw the maples abud.

2.

That was last night.

This evening we get our finances in order,

Play Scrabble, thaw some chicken,

Look askance at the cat,

Consider getting a large dog.

What are we to do with far-off cousins,

Mothers as small as elves

In ranch houses in Bay City?

She irons my suit,

She sorts her jewelry.

I cannot begin to describe my hands

On her inner thighs, nor hers

On mine. What are we to do?

3.

It will not be an easy spring—

The large-footed hound has left his prints,

His bray has entered our sleep,

His coat is as the stars melting above,

Blurred novas, smear.

We dread leaving the house.

We look back. We go.

4.

(First, the ringing in the ears,

Then the voices—the music half-heard.

To jolt awake hearing cantatas, a continuum,

A vacuum. Your name is called.

Called again until you answer.

To wake into a room

You do not know, and then know.

Know too well.)

5.

I love you, she tells me.

I love you more, I say.

I don’t think so.

We take turns having the last word.

We mean what we say.

The world is so suddenly old

Around us, brittle as kindling,

As crisp as burnt wicks.

Let us say we lost language,

Could only signal and act out.

Would the world soften, emerge

Young and darling, sweet to the taste,

Amazed at wetness, even touch?

But we do speak, we say what we mean,

And the world is busy growing gray,

Ashen.

Dinah Berland

HOUSE OF LOST CAUSES

The living room is ringed with masks:

rascal rabbit, industrious donkey, parrot

of good cheer. The man and woman

put them on and walk around the house

talking, not talking. She thinks she's going to die.

He thinks he will go crazy. The kitchen

is bursting with sorrow¯stuffed squash

with sorrow, broiled salmon with sorrow,

sorrow pasta with marinara sauce. They

eat it at lunch. They eat it at supper.

And then they eat some more. How fat

we have become! he says. They laugh

and take the dogs for a walk. What else

are they supposed to do? The bedroom

is a dark blue pool they sink into at night,

faces frozen on other people's words, drifting

into Arctic, Antarctic waters, icebergs

breaking off like pillows

at opposite ends of the world.

![]()

Dinah

Berland

FALLING OUT OF LOVE

Please tell me how it’s done. Do you rip off

your clothes and dive head first into

a sea of naked women? Do you swim out

to the breakers and let the riptide take you?

Or do you just lie there staring at cut flowers,

watching the petals wither and drop?

I did that once with roses when I was stuck in bed

for six weeks. Surprising how petals

shiver and jerk before they fall, how suddenly

things change. One night your teenage son

looks you straight in the eye, next morning

he’s taller than you are. One day your hair is short,

the next it needs cutting. Even babies in their cribs

grow in fits and starts. You’re pregnant or you’re not,

you’re alive one second and dead the next. So maybe

that’s how it happens--in one fell swoop,

like being struck by amnesia. One night

we ’re embracing under shooting stars, the next

you can’t remember who you’re married to.

Dinah

Berland

EXIT ROW

I could grasp the red handle

and ratchet open the exit door, step out

in my terry-cloth slippers, tiptoe

to the edge of the slick metal plank, arms

outstretched like a tightrope walker, lungs

filling with frost. I could pull down

the red flap on the inflatable yellow raft, jump

aboard and waft out over the gently undulating

peneplain so slavishly swabbed by the clouds.

I could slide down those thick black arrows

neatly stenciled over that white painted stripe

and tumble all the way to the ground.

I could, but I won't. I'll keep my

seat belt fastened until the plane shudders

onto the tarmac, flaps pulled back to reveal

rotating knuckles and guts. I'll disembark

in sync with the crowd, propel my body

forward, glide down the escalator, acting

as calm as can be. I'll step outside, where

you will not be at the curb, leaning against

the car, arms folded across your chest

like a nonchalant chauffeur, not speeding

down the freeway from Vernon, hoping

my plane is late. You will not be waiting

for me to fall like a star spit into the void,

not waiting for me anywhere tonight.

Steven

Rydman

AT THE AIRPORT

The woman waits, her dog

sleeping in its boxed cage

at her feet. His shocked fur

lit like a bulb of tan light

reaches for a freedom

that waits outside the bars.

The sun's light slants on her face

as it sets in the west. She will fly,

north, to a dark home,

a sleeping husband. She won't wake him

as she sits by a cracked bedroom window

the flamed tendrils of her red hair

reaching for her reflection

in the smudged glass.

Steven

Rydman

LA FIN DU MONDE

Like rows of coffins, fluorescent lights

line the ceiling, processionals of dead light.

One casket is mine, and I float up into it.

A polyester warmth sizzles around me

a hot shower on fresh sunburn

though my skin is cold,

a blizzard of cerulean snow and shadow.

A pale girl wipes coffee tables around me.

Her blue hair hangs like apocalyptic icicles

creating a blue corona of light to crown her.

She wakes me from my wordless coma.

I ask: What is the most exciting thing you've seen today?

Her face blank as the page I write on.

I'll give you two, she says, coffee grounds and dust bunnies.

The scratchy needle of boredom

skipping in her mouth.

Au revoir, c'est la fin du monde!

She circles away; her white rag erasing everything.

I drift up to the ceiling again

into my blazing coffin.

Au revoir, le monde! Au revoir!

Light caresses skin, a satin lining I lie in

my eyes buried in dusty white clouds

that glow and grow into mouth, melt on my tongue

like rocks of sugar. An artificial buzz rings

the choked whispers of mourners as they pass beneath me,

the heat of their perfumed air rising to my lit nostrils.

![]()

Steven

Rydman

SUPPOSE AT TWELVE, I AM NOT A BOY

But instead, I am a spring leaf

leaning easily on another leaf

drops of sap sticking between us

my chartreuse veins preening

against moist green skin.

Or I am a stamen in a calla lily,

a proud golden rod

gently rubbing tawny dust

on smooth alabaster petals.

Yes, my father's callused palm

is just the brown scratch of bark

protecting with its harsh stroke.

And my mother is a dense thicket

of bushes and pachysandra

cradling our footsteps

and covering the dirt.

Or suppose I am just a boy

with a family of dry stick figures

pressed in black ink

next to a crayon colored house,

crumpled and thrown away

with a child's impatience.

![]()

Jonathan

Hayes

LIKE EYES OF THE TAPSTER

When creation is hot

in the basement of a cool mind,

and dogs run through the street

without leashes or order,

your dark pint remains

unfinished on a wooden bar.

![]()

Jonathan

Hayes

FATHER

The announcement

of freshly-smacked after shave

The contamination

of armpit sweat in a yellow Izod

And the mistake of being human

Eisenhower paragraphs of tight logic

The smell

of coffee in a deli cup.

![]()

Jonathan

Hayes

HARVEST MOON

They come home at night

off rainy streets.

Going into warm apartments

that reek of the past.

And sleep on mattresses

that slowly break them

into the alarm of a tomorrow

heavier than the day before.

![]()

Athena

Kildegaard

FUGUE

Sky all stars, the moon come

full to the upright cemetery,

a shuffling of feathers:

Lie down lie down

between the stones,

beneath a white oak's branch.

Dare to close your eyes,

meet unafraid the dark.

Gravestones proud in their standing

wrestled from granite,

sharp wrought in loss & pain:

how we mourn for the loss,

for what came before pain.

There too is beauty.

Stand ready in the cold,

hands in your pockets,

your breath around your shoulders:

no shadow only a bird,

no bird only an oak,

one tree hiding the moon.

![]()

Athena

Kildegaard

ARMADILLO

Vestigial, half blind, almost

unable to smell what is in her path,

the armadillo has one trick:

she fills her intestines with air

and swims to the farther shore.

Otherwise, if the stream is narrow

she lumbers along the bed,

her claws precarious on the stones,

water flowing across the carapace

that arms her pale flesh.

She tastes something like pork,

this poor swine, this humble throwback

who longs only for the naked grub,

fellow burrower, joint-tenant of the dark.

![]()

Athena

Kildegaard

DEAF SMITH COUNTY, 1932

Trains ground through day and night

loaded with grain and hoof and hoboes.

No one got off, no one boarded;

Herefords and winter wheat held

everyone in place. And the dust storms.

She lay wet dishcloths over the crib

and dust fell in silica layers, forming

a thin board for schoolboys' sums,

fingernails in the dust scratching through

to damp-darkened cloth, my father's

brothers glossing his asthma tent

with hognoses and hangmen's nooses

and the name of the oldest brother's beloved.

So that he, my father, breathed

in that small place, watched the shapes

and scrawls come and go, all backwards,

crabbed and faint. Once, I watched him

put everything he'd ever written in a fire,

word to flame to dust, so he could start again.

![]()

Athena

Kildegaard

ROOSTERS

Hi de hi de

hi de ho at dawn,

pure mojo and love

gone wrong,

a cold bed, but hearts

fierce as swords.

They're strung with lights

and last year's tinsel,

as in a basement club

where the owner---she's big

on her stool by the open door---

lifts a cumbrous chain.

They strut their stuff,

gasconnade the riffs,

grind down the thump,

the hump, the rascally

blood pound of longing

until dawn when

they step out from smoke

and spilled gin

to answer the light.

![]()

CONSCIENCE IS NEVER KIND

The wind is torn by birds

calling for mates.

They settle for fish instead

which the distant sea

forces through earth.

The fish are silver.

Some flap like Kafka's bug.

The birds become hammers.

They break the wind's glass.

A great keening comes from the fish

who now change into all the women

you once desired.

They carry nails disguised as worms.

Joseph

Lisowski

NOT THE BEST WAY TO WAKE UP

Two dogs run down the stairs,

jump at the door and bark

at nothing. A man down the street

hoses his screen door in the rain.

At the corner station, a fire truck

is burning in its garage,

sending great ribbons of black smoke.

They swirl past a boy

standing on his porch.

He

shoots his toy gun at your window.

![]()

Rebecca

Seiferle

THE WARRIOR FOR

LIFE

No, I’m not a warrior. When whatever

I’m battling

vanishes or suddenly turns to me with open arms

and a laugh or a smile, I feel only my own weariness,

and the way the wound within me, after all these years,

is surely turning me to shadow. The battles

were different when I was a child--sword fighting

with a heavy blade and a crosshandle that I fashioned

out of wood, my friends and I astride the lawns

of summer, trading crashing blows, never stabbing

at one another but with a mighty thwack! trying

to shatter the swords. No cruelty in our fury, just

a ferocious energy; we were like fountains bubbling

over into themselves, each drop of energy spent

returning quickly to us, and by day’s end, our arms

and shoulders aching, our knuckles scuffed,

well-pleased, we felt we’d defeated every shadow

in our bright realm: our crusade, just a desire to play

and not be reined back to the fenced yard and the chill

definitions of our parents’ table, where girls with swords

were forbidden or had to disguise themselves as boys.

The Maya believed that women who died in childbirth,

like warriors who died in battle, entered paradise

immediately, but that’s only the valor of death,

so, no, I’m not a warrior. The only time I’ve ever

worn a warrior’s face was when my son was born.

His head was turned, and I had to use the pain

and shudder of my own body like a hand to guide

him out, though it was the hand and arm of the nurse

reaching up into me that grasped gently the crown

of his head and turned him by slow millimeters

for minutes and minutes toward the light. I was glad

for her gentleness, for I had to trust her, to let

my breath and muscles obey her voice as she told me

to wait, to push, to wait again, and all the while

her arm wedged into me was as forceful

and painful as the force contracting my body.

It was a battle she and I were fighting–-myself,

both warrior and battlefield--a fierceness upon

our faces, without crying out, laboring together

until an hour later, with the pushing force of at last

and a mighty groan, his head turned toward this world,

and her arm slipped out, and the baby followed:

all nine and a half pounds of him, his 23 1/2 inches,

spilling out, his limbs drumming with a beautiful fury,

and as everyone did this and that--the cord clipped,

the tear in me stitched, the baby assessed and

bundled, the nurse slipped away quietly with

a pat on my arm, and I was wheeled to another

room where I lay back on the bed and put my arms

above my head and stretched out and smiled,

as if I were lying in a meadow full of flowers

that were only slightly crushed, as when children

roll and play upon the grass and the flowers

spring back up, and my husband took my photo,

and there, on my face, that’s the look of a warrior--

a happy warrior, one who has been victorious

in battling another to life.

![]()

Jnana

Hodson

LOVE POTION TUMBLER FIND

True love doesn’t hit that way, D.L. thought. No, he argued, it starts

slow and builds over years. He envisioned Tessa Logan in Grindingle and

wondered what could possibly be better. But Mitch had called, to say he

needed a place

to stay for the weekend. Said he had found the love of his life. And so,

practical concerns pressed.

"

I’m not sure. I’ll hitch down Friday, don’t know exactly

when I’ll arrive. Depends on the rides."

D.L., meanwhile, needed to discover there’s nothing more glorious

than the many manifestations of intimacy. Mitch said he had to get away

from his

campus a bit.

"

Of course. So what’s the big deal? Is your ex-prima donna, prima

mamma after your tail with a pitchfork?"

"

No, no, nothing like that. It’s simply that Yvonne attends Daffodil,

just like you."

Which is when D.L. realized he’d been indoors too long. When, in

being set up for a magical introduction, he entered a lobby where any wait

would

feel like an eternity. Getting an elevator could take eons.

Yvonne? Didn’t matter. Rather, the spirit wrapped in strawberry and

Dublin-colored suede a step behind her caught his attention. The soft voice

had him hoping to capture each syllable. Whatever pierced him at that time

would affect his memory forever, even if he could remember next to nothing

of what was actually said.

* * *

She was about to sweep away shards remaining from his high school crackup – more

precisely, his breaking up over romance in his senior year. Ever since, his

heart and skull had continued warring, sometimes erupting feverishly into

a death mask mirrored in his own hands. Despite later dates and embraces,

the artistic and social projects he retreated to whenever that suffocating

midnight grip loosened, the self-therapy of hunchbacked miles along thunderstorm’d

sidewalks, the scalding showers, exhausted jogging, throbbing woofers and

shrill tweeters, hours of dreamless sleep – D.L. had never fully

eluded that gigantic amoeba. Disconcertingly, in trying to withdraw, he

rolled back

to his own deficiencies time and time again. The most painful message in

all this, perhaps, was that he could not conquer everything he set out

to accomplish; many things would remain beyond his range or his abilities.

(In that brief, disastrous infatuation he had sought validation. Having

a beautiful, charming, intelligent girlfriend would be a sign of completeness,

of fulfillment. He believed that something in the mystery of woman spelled

salvation, which is, of course, a terrible weight to place upon anyone.

How

could he burden his beloved with his own suffering? Any American boy who

isn’t an athlete is handicapped – especially in the nation’s

heartland. He wasn’t sturdy enough for football or even basketball,

swift enough for track or cross-country, forceful enough for baseball, at

least for the success he demanded of himself. He knew these activities weren’t "play," despite

usage, and believed only victory would compensate pain and exertion. His

strengths and speed lay elsewhere. But you remained loyal to people and institutions.

Adolescent birds leave nests and stake out new territory. He yearned for

loving, a special acceptance. He spent weekends in grandstand choruses, screaming

himself hoarse in spectacles where he was cast as a eunuch rather than a

warrior who could claim spoils – nights memorizing contours of smooth

legs, dreaming of kingdoms and harems, power, authority, and consolation.

The more his activities had taken him along their corridors, the more petty

jealousies he discerned; rather than piety and devotion, there were raw

politics. Dogma he embraced did not lead to angels. Yet, when fundamentalist

Doris

began flirting, he anticipated multidimensional glory, hoping not only

for salvation in her woman-spirit, delights of her smile and torso, and

prestige,

but also for strength through her convictions. He had expected too much.

When her friends revealed how she had lied, something besides love soured.

A rocket exploded on take-off. A facade collapsed, taking sky and street

with it. A giant fish had been caught not for feasting or trophy but to

rot in sun. In a pulpit he could no longer speak what he believed. He could

not

proclaim his metamorphosis without wrecking everything at home. He remained

strictly honest, however covertly, by directing hootenannies, film festivals,

picnics, and dances. When the academic year ended, he never again entered

that congregation.

And now, this brilliant Lumina in other fields was setting out to encounter

fair Disillusionment in this young woman named Pepper. She, too, was ready

to set forth, needing only someone who could appreciate her interests, which

overlapped with much of his own dreaming.

In short, he had it - and had it bad. She knew a suitor had come, and he

was all hers.

As a second Joint Venture moved closer to publication, D.L. was asked to

design a psychedelic cover. These days, thanks to Pepper, he saw only stars.

This time around, there was nothing symmetric. In fact, everything was unbalanced

- like life.

Now, at last, all the past was countered, all his yearning reversed, all

had seemingly healed, all was waiting to happen again.

![]()

.jpg) Peter Hobbs

copyright 2003

Peter Hobbs

copyright 2003

Dong Soo Choi

copyright 2003

Dong Soo Choi

copyright 2003  Dong

Soo Choi copyright 2003

Dong

Soo Choi copyright 2003Danny

Rendleman's last book was THE MIDDLE WEST. Recent poetry and fiction

can be found in The Isle Review, Facets, Marlboro Review, and

Drought. He teaches rhetoric and creative writing at UM-Flint.

Dinah Berland's poetry has

appeared in The Antioch Review, The Iowa Review, Ploughshares,

and Margie, and won second prize in Atlanta Review's

2003 International Poetry Contest. She received her MFA from Warren WilsonCollege,

a fellowship from the California Arts Council, and works as a book editor

for Getty Publications in Los Angeles.

Steven Rydman is currently

working on his Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at Antioch University

Los Angeles. In the summer of 2000, he was named the Grand Prize Winner

in the Detroit Metro Times' Fiction and Poetry Issue. In 2001, he received

a Commendation Award in the Allen Ginsberg Poetry Awards given by The

Poetry Center at Passaic County Community College in Paterson, New Jersey,

which included publication in The Paterson Literary Review. More of his

work has appeared in Rattle and Connecticut River Review.

Jonathan Hayes is the author of ECHOES FROM the SARCOPHAGUS (3300 Press,

1997) and ST. PAUL HOTEL (Ex Nihilo Press, 2000). Recently published by

Sidereality, Some Words and Unlikely Stories; he edits

the literary / art magazine, Over the Transom.

Athena Kildegaard lives

in Morris, Minnesota. Her poems have been published in several journals

including Faultline, The Malahat Review, Puerto del Sol and

The Florida Review.

From 1986 to 1996, Joseph Lisowski

was Professor of English at the University of the Virgin Islands. St.

Thomas serves as the setting for Looking for LISA, his recently published

novel now available from Fiction Works (http://www.fictionworks.com).

Dr. Lisowski is now teaching at Elizabeth City State University in North

Carolina. Recent chapbooks include Letters to Wang Wei, along

with two essays, (Words on a Wire); After Death’s Silence

(2River View); and Grief Work (Kota Press), JB, a dialogue

in poem form between John the Baptist and King Herod (PoetryRepairShop),

and Stashu Kapinski Strikes Out (Rank Stranger Press).

Rebecca Seiferle is the publisher of The

Drunken Boat, an online literary quarterly. She teaches English

and creative writing at San Juan Community College and is listed with

Tumblewords, the New Mexico Arts Program. She lives with her family in

Farmington, New Mexico. Her third poetry collection, BITTERS, published

by Copper Canyon Press, won the Western States Book Award and a Pushcart

prize.

![]()

Jnana Hodson’s prose

has also appeared recently in Jack Magazine, Hobart, La Petite Zine,

Organic Literature Experiment, and The Sidewalk's End.

Peter Hobbs is the Photography

Counsel at Portfolio

Center, in Atlanta, Georgia. Visit his Web site at: Peter

Hobbs Photography

Dong

Soo Choi is a professional photographer who lives and works in Atlanta,

Georgia.

Welcome to Blaze, a quarterly magazine of literature and visual art. Here, you will find well-crafted, provocative pieces from established as well as emerging writers and artists.

We're interested in your feedback, so please drop us a line if you want to rant or rave.

All work is the property of the authors/artists and may not be reproduced without permission.

This site was designed by Rachel Cellinese, in DreamWeaver, and is best viewed in Safari or Explorer.

All rights revert back to the contributor upon publication, but we'd appreciate the courtesy of acknowledgment if your work is published elsewhere.

We will respond within 6 weeks and ask that you not submit again before you've heard from us about the first batch.

Please send poems and stories in the body of the email (We will not open attachments) and include a short bio that includes any recent publications.

Poetry

3-5 pieces, no more than 100 lines each.

Flash Fiction

No more than 2 stories, 300-1000 words each.

Photography

Up to 10 images. Send a jpeg of your photo at

72 dpi and 400 X 500 pixels.

Interviews, book reviews, and essays

Please query.

Email all work to Blaze submissions Blaze Submissions

Editor-in-Chief: Tania Rochelle

Poetry: Dawn Gilchrist-Young, Dawn Lee

Flash Fiction: Sam Harrison

Links

The Drunken Boat

The Marlboro Review

Three Candles

![]()

![]()

.jpg) Peter Hobbs

copyright 2003

Peter Hobbs

copyright 2003